Haiyi Xie

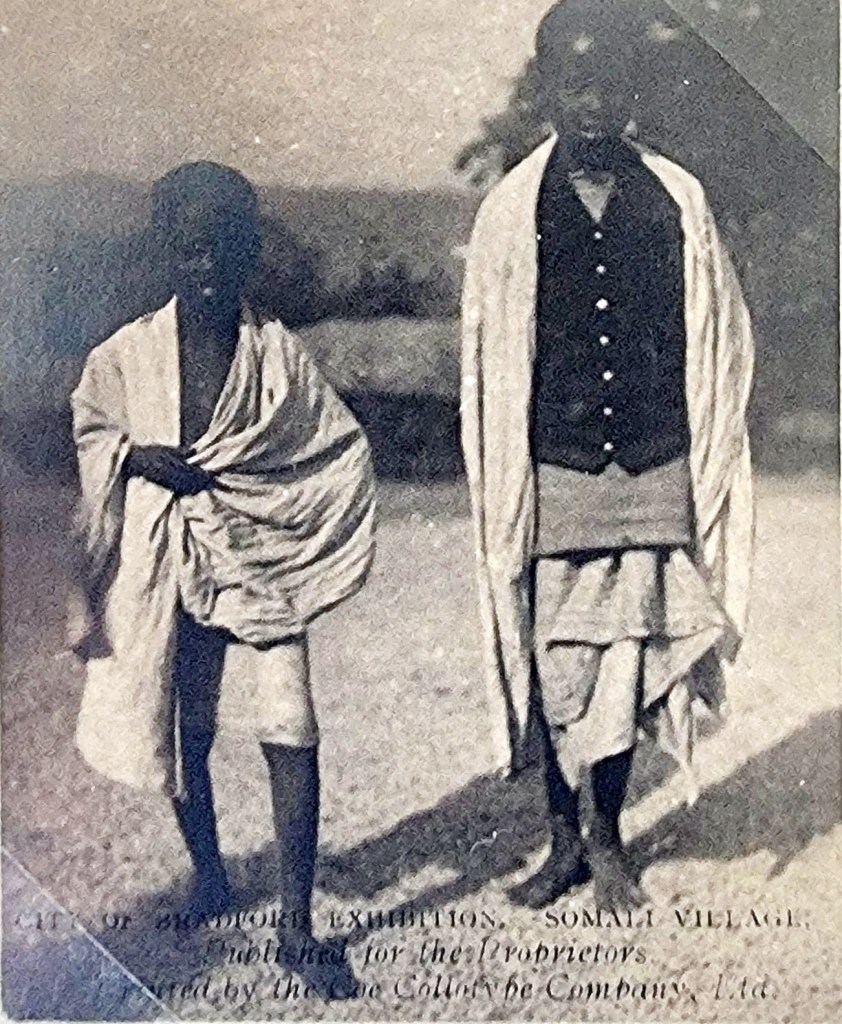

In Bradford in 1904, a group of Somali workers arrived to perform aspects of their culture to satisfy British curiosity about Somaliland, which they had recently invaded. A surprising number of these performers were children.

In this blog, I want to focus on the children who grew up in the Somali village in Bradford for two reasons. Firstly, examining this specific group of Somali children is valuable due to their unique circumstances as ethnographic performers. The psychological development of all children is critically shaped by their environment, which influences their perceptions and behaviours. At the same time, children are often more adaptable than adults, who have already formed solidified perceptions, allowing them to adjust quickly to new surroundings. So, the childhood experiences of these Somali children in Bradford are particularly noteworthy because they were exposed at a young age to the gaze of colonial powers through acting as representatives of Somali culture. These children had to navigate between distinct Somali and British cultures in the artificial environment of a staged “native” village. Another reason that I focus on these children arises from humanistic concerns. Colonialism likely caused more harm to children than adults, as these young individuals participated in tours due to the selfish interests of the colonisers and, in some sense, their elders. Unfortunately, as the historical record of the Village is almost entirely dominated by the Yorkshire archive, I can only present a general portrait of these children, portraying their work, studies, and family life, as observed through the eyes of their colonisers.

Several newspaper reports mention that during their six-month residence as part of the Bradford Exhibition, the Village’s children took responsibility for selling programme books rather than performing. They showed a willingness to use their talents to earn money. They used their linguistic skills to pick up some English quickly to make jokes for tips or kept a halfpenny for themselves when giving change. In a report by The Shipley Times and Express, it says,

The children especially are very pretty and plump, and they are very well-behaved, with the exception of their constant requests for “backsheesh,” which they playfully urge upon everyone. Many of them show an intelligent aptitude for learning English, and now and again, you can catch an English word in their conversations.[1]

Similarly, the Bradford Daily Argus notes,

One thing that all visitors to the village will notice about these Somali youngsters is their quick understanding of the value of English money. The sharp programme boy, for instance, is an impressive hawker. He is clever enough to try to gain a copper when giving change, but a visitor who attempts to negotiate with him regarding money will find it a challenging task. Another little boy approaches you in a business-like manner, asking for sixpence, having a handful of coppers in hand. He is really after a piece of silver, and if a visitor obliges, they may discover they receive only 5 1/2d in copper in exchange for their “tanner.”[2]

Adult Somali males, on the other hand, prided themselves on refusing handouts, viewing them as an insult.

In addition to soliciting change from tourists, the children also attended school. The Somali performers established a school in the village specifically for the children, staffed by Somali teachers. They aimed to educate the children in their own culture and beliefs, where they were “taught to recite portions of the Koran and lessons from the Hafiz [Hadith].”[3] The results of this education are promising:

The copybooks of some of the children would do credit to any English school in terms of neatness and cleanliness. The writing is done in ink with a home-made pen, resembling a page of neatly written shorthand. The letters are Arabic, and the language is Somali. One scholar even wrote an essay about a chicken.[4]

Additionally, a clip showing the children demonstrating their learning ability reveals they were also taught elements of British culture:

To illustrate the children’s aptitude for knowledge, a young boy was introduced to an ARGUS representative, and with almost perfect pronunciation, he recited the first verse of the National Anthem. Although an attempt was made to teach the correct tune, he sang it in a style similar to a native chant.[5]

Unfortunately, this report also highlights the author’s colonial biases, as he disrespectfully refers to the child who sings the British national anthem as a “patriot” and expects him to sing it in the British manner rather with his traditional Somali technique.

Outside of school and work, the children bring their lively natures back to the traditional Somali family, which, while warm, can also be harsh. The author recalls witnessing a child chased by his father and judged by his clan for interrupting a ritual with his playfulness. The strict discipline of children within Somali culture is often questioned by the British, who fail to understand Somali parenting norms.[6]

A girl’s interaction with her mother illustrates the tender side of the Somali family:

When the food was ready, it was served in different dishes, some sugar sprinkled over it, along with a yellow liquid resembling egg yolk. The little girl ran and tasted from each bowl, and when her mother poured out a volley of reproaches, the girl unconcernedly took a handful of the mixture and skipped out of the woman’s reach. This little trick, performed with such playfulness, caused the mother to forget her anger and burst into laughter.[7]

As shown from these contemporaneous press reports, the children are portrayed relatively positively as showing remarkable adaptability and talent, along with their spirited nature, in contrast with the Somali adults who are largely depicted as solemn and tradition-bound. The children sought out tips from the audience and took risks, knowing they might be punished for their mischief. They studied Islamic texts in Arabic and sang the British national anthem in a spirited chorus. Despite their status as colonized individuals subjected to scrutiny, their clever and mischievous spirits are not completely suppressed in the colonial archive, allowing us to glimpse the Somali children carving out their own place in a difficult situation.

I have two reservations regarding this blog. Firstly, all the historical materials referenced are British accounts of the Somali villagers, which inevitably reflect the coloniser’s perspective on the colonised. This leaves me feeling uneasy about perpetuating a colonial viewpoint. Secondly, the available materials only relate to the children’s lives in the village, and I am equally concerned to find out what happened to them after leaving the Somali Village, as well as the longer-term impact this had on their lives. I hope to invite Somalis, especially the descendants of those who were part of the colonial experience, to share their memoirs and provide commentaries from a Somali perspective to address this gap in understanding.

Haiyi Xie is a 2nd year Liberal Arts Student at the University of Leeds, and is part of the student team on the research project “A Somali Village in Colonial Bradford”.

References

[1] Shipley Times and Express, 10 June 1904, p. 5.

[2] Bradford Daily Argus, 9 May 1904, p. 3.

[3] Bradford Weekly Telegraph, 21 May 1904, p. 1.

[4] Bradford Daily Argus, 9 May 1904, p. 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Bradford Daily Telegraph, 16 May 1904, p. 2.

[7] Jackdaw, 4 Aug 1904, 1/17, p. 18.