Yahya Birt

A Fire Breaks Out…

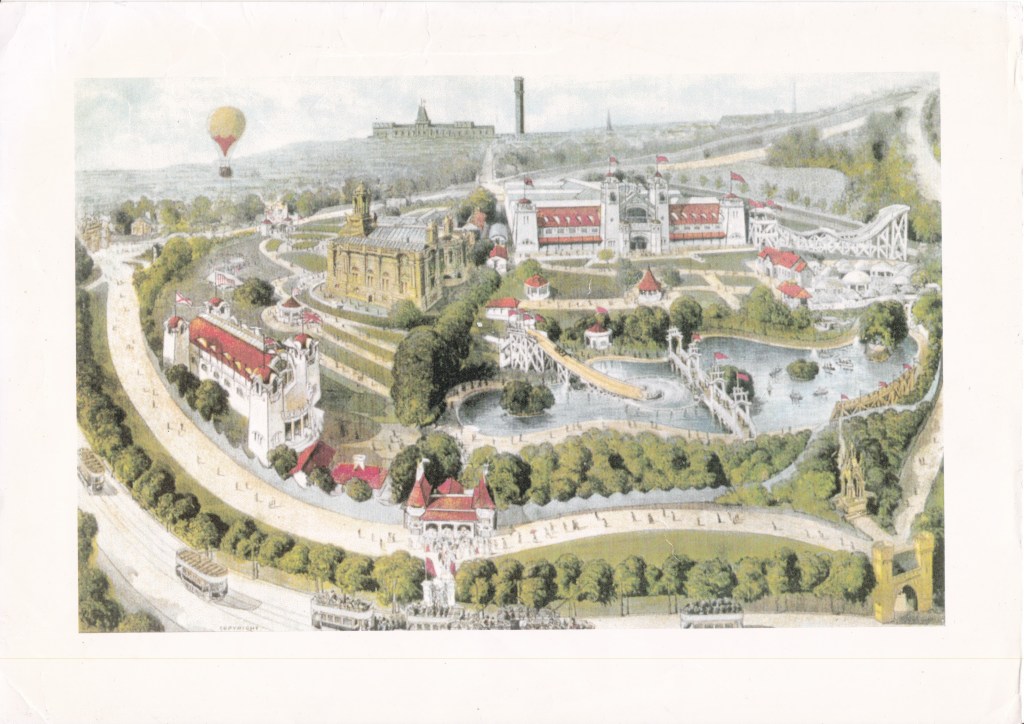

In the late summer afternoon of 30 August 1904, a fire broke out at the Somali Village in Lister Park, the most popular attraction at the Great Bradford Exhibition. The leader of the Somalis, Sultan Ali al-Urfa, and Mr. Singer, Secretary to the company, British & Continental Enterprises Ltd, which ran the Village as a concession, discovered the fire early on. It had started in one of the Village huts that backed onto the compound wall. The fire was spotted just after the Somali men had finished one of their five daily Islamic congregational prayers (‘Asr, the late afternoon prayer). As there were no fire extinguishers to hand, the fire spread and destroyed four huts and their contents before being put out, once the Fire Brigade was able to bring fire hoses down to the Village from the Industrial Hall, further up the slope that Lister Park lies on. When the fire broke out, the Village believed that a four-year-old Somali boy, Farah Hassen, had been trapped inside one of the huts. It caused great distress, but, much to the relief of the troupe and his distraught father, Hassen Abdullah, he was discovered to have taken refuge under a fruit stall.[1]

As two of the four destroyed huts were used to store the troupe’s valuables, acquired in France and Britain, some £200‒£300 in value, their destruction was costly for the Somalis, especially for Sultan Ali who lost all of his valuables. The Bradford Daily Argus reported that:

his silk robes, embroidery, blankets and personal ornaments [were destroyed]…. He most regrets the loss of the formidable but picturesque dirk which he usually wore at his side. This was made in Abyssinia, and was richly carved and ornamented. His total losses will reach something like £200, and as most of the warriors stored their valuables in the Sultan’s “strong room” their loses will aggregate another £100.[2]

At the time, reassurances were given in the press that the loss would be covered by third-party indemnity insurance, provided by the company running the Village as a concession. Without any surviving company archives, it is hard to corroborate or make sense of the claim when the West Yorkshire archive has correspondence that the city itself made an insurance claim for goods lost in the fire. Was this a false promise made by the company to the Somalis? Was it simply a case of misreporting by the local press? It is not possible to say.

Furthermore, the actual amount claimed for lost clothing by the city on 2 September was a mere 5% of the original amount stated in the press. £11 was claimed from the insurers for two complete suits, three pressed trousers, and three caps.[3] While the archival evidence is silent on the reason for this large discrepancy in the valuation between the claims of the troupe and the city, it created significant resentment among the Somalis.

Furthermore, no adequate investigation of the fire’s causes was ever conducted. At the time, two possible causes were aired in the press. The first was speculation that the blaze had started due to a faulty electrical wire.[4] The other allegation was made by George Bilson in a letter to the Bradford Daily Telegraph, who worked the postcard stall at the Somali Village for H.M. Trotter & Co.[5] Bilson wrote that his repeated warnings to visitors, including on the night of the fire, not to give matches to the Somali boys to play with as “toys” were continuously ignored by members of the public, as he feared it would lead to a conflagration that did indeed occur.

The only official report into the incident by the Fire Brigade Commission only dealt with the narrow question of whether any responsibility for the spread of the fire could be attached to the Brigade because of the slowness of its response. The report roundly rejected this conclusion, although, on the face of it, the recorded timings do indicate delay due to the need to get water hoses down from the Industrial Hall. Sultan Ali and Mr. Singer discovered the fire at 7.15 pm and immediately reported it. They and others, including the Chairman of the Executive Committee, Councillor William Lupton, then made unsuccessful attempts to contain it. The fire was independently verified at 7.22 pm; the Gamewell alarm was only sounded at 7.30 pm; and the Brigade only arrived at the scene by 7.39 pm with hoses. By this time, a crowd had already gathered, which impeded access. Released in early October, the report did not address either (a) the cause of the fire or (b) the lack of extinguishers at the Somali Village.[6] The day after the fire, the lack of onsite fire suppressants was rectified, and the Somalis received training in the use of extinguishers, successfully putting out another small fire at the neighbouring Naval Show the following night on 31 August.[7]

The Somali Town Hall Picket

The perceived shortfall in compensation and the lack of formal investigation laid the grounds for the Somali picketing of the Town Hall on the day of their departure for Hull from Bradford Interchange to take a ferry to Rotterdam, and from there to board the SS Kanzler on 3 November on the German East Africa Line to Aden.[8] They had been scheduled to take a special train to Hull at 2.35 pm (with an additional coach to carry the disassembled Village huts), which was delayed by 40 minutes because of the unresolved dispute at the Town Hall.

It is reasonable to infer that Sultan Ali, in consultation with the troupe, carefully planned the timing and location of this picket. A highly visible protest outside the Town Hall on the day of departure ensured it would be reported, thereby maximising the possibility of public embarrassment for the city council (the organisers of the Exhibition), which turned out to be the case as it was reported in detail in the local press over two days. Also, as the picket was done after the Exhibition had officially closed, no counter-claim could be made against the troupe for breach of contract for leaving the Village without permission.

Additionally, the troupe charged Victor Bamberger with letting it down in a second matter of compensation – the wages due for its period of travel between Somaliland and Europe. Thus, the Somalis appealed to the Lord Mayor, the most senior figure in the council, to make their case for a shortfall in wages against their employer, Mr. Bamberger, and against the Executive Committee of the Bradford Exhibition for the shortfall in insurance compensation. It showed the troupe calculated that both Bamberger and the Executive Committee could be held accountable by involving the Lord Mayor.

Leaving the picketing men outside the Town Hall, Sultan Ali and the Mullah sat down to discuss their claims with the Lord Mayor, William Lupton, the Chair of the Exhibition’s Executive Committee, Victor Bamberger and Charles Hastings. Both claims were quickly rejected, and it was suggested that the Somalis were to blame for the fire, but nowhere in the press is any detail provided as to how and why, let alone any evidence. While the picket failed to achieve its aims, it also offers ample evidence of Sultan Ali troupe’s view of the tour as a business arrangement for which services and losses were to be fairly compensated.[9]

When framing the Somali Town Hall Picket of 1904, it can be linked concretely to other forms of labour protest in Bradford, such as the Manningham Mill Strike of 1890–91. If we follow Sven Lindqvist’s advice to unearth buried labour histories then, despite the racial assumptions of Edwardian Bradford, it is easier to see the shared colonial system that bound the mill workers and the Africans they saw in Lister Park in regimes of economic exploitation (for more, see Bradford’s Wool as a Settler Colonial Commodity).[10]

Yahya Birt is a community historian of early Muslim life in Britain.

References

[1] Bradford Daily Argus, 31 August 1904, p. 3; Leeds Mercury, 31 August 1904, p. 6

[2] Bradford Daily Argus, 31 August 1904, p. 3.

[3] Correspondence, W.H. Knight, Manager of the Bradford Exhibition to Messers A.W. Bain and Sons of Park Row, Leeds, 2 September 1904, WYAS Bradford – BBD/1/1/48/1 – Bradford Exhibition 1904 – Gen. Admin Manager – Letter Book, Vol. 2.

[4] Leeds Mercury, 31 August 1904, p. 6.

[5] Bradford Daily Telegraph, 1 September 1904, p. 3.

[6] Bradford Daily Telegraph, 10 October 1904, p. 6.

[7] Bradford Daily Telegraph, 1 September 1904, p. 6.

[8] Advert for Deutsche Ost-Afrika Linie [German East Africa Line], Rotterdamsch Nieuwsblad, 22 October 1904, p. 2.

[9] Bradford Daily Telegraph, 31 October 1904, p. 3; Shipley Times and Express, 4 November 1904, p. 4.

[10] Sven Lindqvist, “Dig Where You Stand”, Oral History, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Autumn, 1979), pp. 24–30, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40178565; K. Labyurn, “The Trade Unions and the Independent Labour Party: The Manningham Experience”, in J.A. Jowitt and R.K.S. Taylor (eds.) Bradford 1890‒1914: Cradle of the Independent Labour Party (Bradford: Bradford Occasional Papers No. 2, October 1980), pp. 24‒44.