Maxie Allen

The story of the Somali workers’ trip to Yorkshire reaches far back into the colonial history of Europe and Africa, and all the way forward into the lives of migrants in Bradford today. In trying to weave this story, I’ve found myself pulled down snickets, sidetracked into obscure ginnels of history. The traces left behind by the 57 Somali workers demonstrate a certain proud agency in surviving exploitative employment.

I must start this story of migration somewhere, and I’d rather start it with Hersi Egeh Gorseh than yet another white male coloniser. Gorseh was a Somali tribal chief who, in collaboration with German businessmen, recruited Somali performers for an 1895 ethnographic show in Hamburg. He was paid well for this work, and became lifelong friends with some of his European colleagues. He recruited performers from his inner circle, and for years this troupe travelled around Europe, honing their skills. Bodhari Wasame, a Somali researcher within this project, suggests many reasons for individuals to have undertaken these journeys; to earn more than at home, to see the world, to represent Somali heritage and warriorship.[1] Hersi Gorseh, in pioneering these tours, ended up with the name “Hersi Arwo” – a Somali word meaning “exhibition”, which in turn gave its name to the distinct profession of the Arwo, spelt “Carwo” in Somali, or “the people of the fair”.

This said, I do not want to downplay the colonialism that landed the Somali troupe in Bradford – the popular phrase “we’re here because you were over there” was as true in 1895 as it is today. Europeans were fascinated by the so-called “colonies”, an interest that sparked this recruitment for wildly successful ethnographic shows, including Bradford’s 1904 Exhibition. This speaks to the experience of so many migrants. The West promises travel and work, while exploiting the labour of those whose homelands have already been exploited. 18.7% of Bradford’s population today is non-UK born,[2] and many of these same complex motivations may have drawn them to the city, both the allure of a better life and the neo-colonialism that exploits migrant workers.

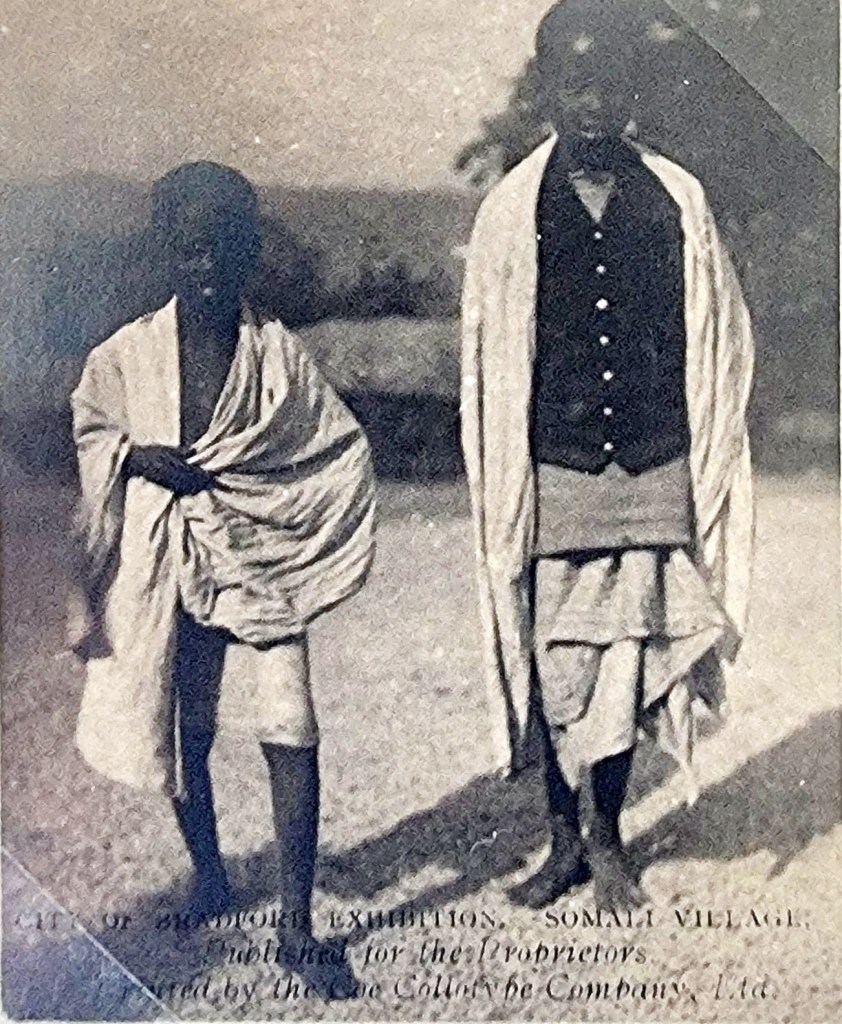

Once the troupe made it to Bradford, they joined the enormous workforce running the Great Exhibition at Lister Park. As the compound they lived in was open to the public, everyday tasks like washing and cooking were as much a part of the show as the spear throwing demonstrations the villagers performed. The voices of the troupe are missing from the archive, but it is easy to imagine how, as Bodhari Wasame suggests, ‘the Somalis cleverly exploited […] their ethnic differences’,[3] giving white onlookers the exotic experience they were looking for. This performative Africanness earned them various rates of pay, starting at £7‒12 for the six months’ work, all the way up the troupe leader’s, £42. Although still earning a low wage, male mill workers at this time outearned the Somalis, making about £20 in 6 months. Female mill workers would earn half a man’s wage, like the rates of pay in the Somali village.[4] While there is no record of gendered pay grades within the archive, I do wonder if gender and race intersected in the lives of Arwo women to create a unique financial handicap, as is the experience of many migrant women today.

There were opportunities for supplementary income within the compound, with photo opportunities and traditional handicrafts sold to visitors. This level of entrepreneurship points us to two aspects of the villagers’ lives – the inadequacy of their wages and the business acumen they possessed.

The full extent of the troupe’s proud agency was expressed on 31 October 1904. After a fire destroyed four of the huts in the compound, two of which contained valuables, the villagers took to the steps of the town hall to demand compensation. This protest places the troupe firmly in Bradford’s long history of workers agitating for their rights. Just 14 years earlier, the Manningham Mills strike had taken their struggle for fair wages to the same spot, also marching into the town centre from the Manningham area, the site of Lister Park where the Somali Village was. At pickets in Docker’s Square, crowds of 90,000 gathered to hear union leaders speak.[5] The strike, although unsuccessful, would change British politics forever. The formation of the Bradford Labour Union came a month after the strike failed, and by 1893 had formed the Independent Labour Party. The working classes of Bradford had realised that both Liberal and Conservative political leaders could not advocate for the interests of workers.

The mill owner at the heart of the Manningham Mills strike was none other than Samuel Lister, who had gifted Lister Park to the city only 20 years earlier. Following the scandal of the strike, the city needed to preserve its reputation and industrial relevance and decided to stage the Great Exhibition. It is easy to imagine that Samuel was equally eager to save face and attach the family name to a win for the city. And so, in 1904, the Somali troupe arrived in Manningham, but didn’t leave without causing another scandal. Without access to the thoughts and feelings of those 57 people, we are left to speculate about whether they were aware of the area’s political history. To fantasise about worker solidarity here may be naïve given the racism the troupe suffered, but perhaps local people advised them to picket the town hall. Either way, the proud dignity of the Somali workers has ensured their story can be read as part of the worker’s resistance to exploitation that shaped the labour movement in Yorkshire.

Their legacy echoes down to the lives of those who adopt Bradford as their home now, and find themselves in precarious, poorly paid work compared with their British peers. I hope that all workers, migrant or otherwise, find encouragement in the bravery of Bradford’s Somali visitors, and advocate for their own rights accordingly.

Maxie Allen is involved in various food justice projects in the city of Leeds, where she is also studying for a Liberal Arts degree at the University. She is passionate about Yorkshire, both its folk and political history and the grassroots organising of present-day communities.

References

[1] Bodhari Wasame, ‘A Brief History of Staging Somali Ethnographic Performing Troupes in Europe.1885-1930’, in Staged Otherness: Ethnic Shows in Central and Eastern Europe, 1850‒1939, edited by Dagnoslaw Demski and Dominika Czarnecka (Prague: Central European University Press, 2022), pp. 77–100 (p. 79).

[2] “12 Migration Related Insights from the Census 2021 for Yorkshire and Humber”, Migration Yorkshire, 2022, https://www.migrationyorkshire.org.uk/12-migration-related-insights-census-2021-yorkshire-and-humber, accessed 28 March 2025.

[3] Warsame, “A Brief History”, p. 89.

[4] George Henry Wood, “The Statistics of Wages in the United Kingdom during the Nineteenth Century. (Part XV.) The Cotton Industry”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 73/2 (1910), pp. 39‒48 (p. 42).

[5] Keith Narey, “The Great Manningham Mills Strike, 1890”, Marxists.org, https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/narey/1978/08/mannmills.html, accessed 31 March 2025.