Yahya Birt

In the early 19th century, Bradford emerged as a powerhouse of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, becoming the nation’s leader in mechanised wool spinning. Wool was the town’s lifeblood; by 1881, a third of Bradford’s working men and two-thirds of its working women were employed in the trade. While Manchester was known as “King Cotton”, Bradford earned the moniker “Worstedopolis”.

Unlike cotton, which is widely associated with the slave plantations of the Americas,[1] wool still carries a romanticised image as a traditional, local product tied to Britain’s pastoral heritage. Wool is even tied up with the myth of Bradford’s foundation, as a “broad ford” where medieval sheep drovers on their way to York settled when they found the soft waters of the stream, Bradford Beck, ideal for preparing the fleece for sale.[2] However, during the 19th century, wool was transformed into a colonial commodity. The mechanisation of wool combing in Yorkshire helped drive the global expansion of sheep farming, fuelling settler colonialism across the world. From the Scottish Highlands to the plains of Western America, and from Australia to South Africa, wool production required vast tracts of land – land that was often violently seized from its original inhabitants.

Peter Wolfe captures this economic force behind settler colonialism as

the driving engine of international market forces, which linked Australian wool to Yorkshire mills…. The Industrial Revolution, misleadingly figuring in popular consciousness as an autochthonous metropolitan phenomenon, required colonial land and labour to produce its raw materials just as centrally as it required metropolitan factories and an industrial proletariat to process them, whereupon the colonies were again required as a market.[3]

Yorkshire’s Role in the Colonisation of Australia

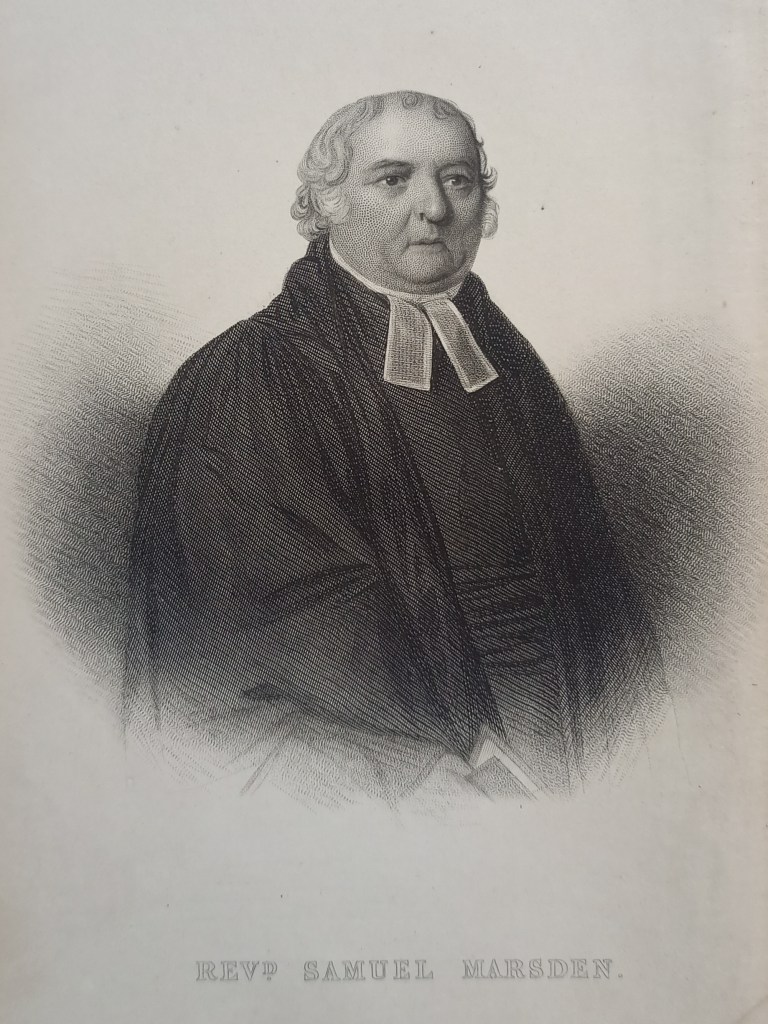

Australia exemplifies this connection between Bradford’s wool trade and British colonial expansion. Yorkshire played a central role in introducing sheep farming to the penal colony of New South Wales, with Rev. Samuel Marsden (1765–1838, pictured), an Anglican priest from Farsley, near Bradford, at the helm. Marsden, who combined roles as a missionary, magistrate, and agriculturalist, brought the first consignment of Australian wool back to Yorkshire in 1807 – a modest 165 pounds packed in barrels to a Mr. W. Thompson, a cloth manufacturer in Horsforth. In 1811, Marsden sent through the first consignment of Merino wool, sold at Garraway’s Coffee House in London, which inaugurated Britain’s Colonial Wool Sales.[4]

Over the following decades, Australian wool production exploded. In 1831, Australia supplied 8% of Britain’s wool; by 1851, it accounted for half of a vastly increased total.[5] By the 1880s, Australia exported three times as much wool as Britain produced domestically.[6] British wool traders operated with offices in the home country and Australia and bought ships to transport their wool and finished goods. Bradford’s textile industry know-how helped to develop the Australian trade directly, for example, Richard Goldsborough, a Bradford wool stapler, introduced wool auctioning to Melbourne in 1849.[7]

This Antipodean connection was celebrated with the inauguration of Bradford’s City Hall in 1873 when the trades, led by the woolpackers, processed from Lister Park to the new Town Hall: Aussie drays of wool featured, pulled by a carthorse and draped with banners and flags (pictured).[8] However, this imported Australian wool came at a devastating cost.

The Human and Environmental Toll

The colonisation of Australia was premised on the doctrine of terra nullius – the claim that the land was “empty” and thus available for settlement. This legal fiction ignored the presence of Aboriginal peoples, who were offered no treaties or protections. From the 1830s onwards, settlers known as “squatters” seized vast tracts of land, displacing Aboriginal communities through violent conflict, forced removals, and exposure to foreign diseases.

The impact was catastrophic. In Tasmania, for example, Aboriginal communities were almost entirely eradicated by sheep farmers. By 1900, the population of Aboriginal Australians had fallen to just 100,000 – a mere 5–10% of the pre-colonial population.[9]

Bradford’s Imperial Economic Legacy

The wool industry made Bradford wealthy, but this wealth was inextricably linked to the exploitation of both people and environments across the British Empire. The city’s wool mills depended on the global system of settler colonialism, which reshaped landscapes and devastated Indigenous populations to meet the demands of industrial production.

In addition, Bradford’s two leading mill owners, Samuel Cunliffe Lister, Lord Masham (1815‒1906) and Sir Titus Salt (1803‒1876), had substantial international interests in Europe and the colonies: the former in Indian silk estates and the latter in opening up the Peruvian alpaca wool trade. In 1857, Salt circumvented the Peruvian embargo on the export of alpaca to Australia (as well as to South Africa) by purchasing a flock from the Earl of Derby and sending it to his nephew, John Fredrick Haigh, a sheep farmer who had emigrated there in 1848; today, Australia is the second largest producer of alpaca wool after Peru.[10] They were hardly alone in this regard as Bradford mill owners had global interests in sheep wool and other products too. Lister’s attempt to keep parity between Bradford and German wages led to the great Manningham Mills Strike of 1890‒1, after wages were squeezed and production increasingly mechanised.[11] Poorly unionised, the breaking of the strike after 19 weeks contributed directly to forming the Independent Labour Party in January 1893.[12]

While this international aspect of Bradford’s economic history has often been overlooked, it is a crucial part of understanding the city’s rise to prominence during the Industrial Revolution. As we reflect on Bradford’s imperial past, we must also consider the legacies of this history: the displacement of Indigenous peoples, the environmental degradation caused by monoculture farming, the enduring inequalities between the Global North and South, and the exploitation of mill labour in Bradford which helped to reshape Britain’s party political system in the 20th century with the rise of the Labour Party.

Yahya Birt is a community historian of early Muslim life in Britain.

References

[1] The role of Tory Radical Richard Oastler (1789‒1861) of Huddersfield in 19th-century campaigns against child labour and Transatlantic slavery is assessed in J.A. Hargreaves and E.A. Hilary Haigh (eds) Slavery in Yorkshire: Richard Oastler and the campaign against child labour in the Industrial Revolution (Huddersfield, Yorkshire: University of Huddersfield, 2012).

[2] J. Butterfield, “Bradford and Wood” in The Bradford Wool Exchange: An Oral History of the Building and Its Role in Bradford, ed. by T. Palmer (Bradford: Waterstones, 1997), p.xiii.

[3] P. Wolfe, “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native”, Journal of Genocide Research, 2006, 8:4, pp. 387‒409, DOI: 10.1080/14623520601056240, quote at p. 394.

[4] W. Hustwick, “Two pioneers of Australian Wool”, Journal of the Bradford Textile Society, 1959‒60, p70; West Yorkshire Archive Service [WYAS], B920 MAR 25.

[5] J. Belich, Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Angloworld, 1783‒1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 278.

[6] W. Cudworth, Worstedopolis: A Sketch History of the Town and Trade of Bradford (Bradford: W. Byles and Son, 1888), pp63‒64; G. Firth, “The Bradford Trade in the Nineteenth Century” in D.G. Wright and J.A. Jowitt (eds), Victorian Bradford: Essays in Honour of Jack Reynolds (Bradford: City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council, 1982), pp. 7‒36; quote at p. 19.

[7] J. Gillison, Wool and Ships: The Story of John Sanderson & Co. (Melbourne: John Sanderson & Co., 1958), p. 8.

[8] H. Hird, Bradford in History (Bradford, 1968), pp. 104‒124.

[9] M. Shaw and T. FitzSimons, “The Fabric of War: Wool and Local Land Wars in a Global Context”, (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1129. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1129; L. Ryan, “‘No right to the land’: The role of the wool industry in the destruction of aboriginal societies in Tasmania (1817‒1832) and Victoria (1835‒1851) compared” in Mohamed Adhikari (ed.) Genocide on Settler Frontiers: When Hunter-Gatherers and Commercial Stock Farmers Clash (War and Genocide, no. 22.) (New York: Berghahn Books, published by arrangement with UCT Press, 2015), 2015.10.1515/9781782387398-010, pp. 185‒209.

[10] Rev. R. Balgarnie, Sir Titus Salt, Baronet: His Life and Its Lessons (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1877), p46; A. Cattell, Sir Titus Salt and Sons: A Farming Legacy (Bingley, 2017), p. 66ff.

[11] A. Briggs, “Introduction”, in M. Keighley, A Fabric Huge: The Story of Listers (London: James & James, 1989), pp. 6‒8.

[12] K. Labyurn, “The Trade Unions and the Independent Labour Party: The Manningham Experience”, in Bradford 1890‒1914, eds. Jowitt and Taylor, pp. 24‒44.